What is Quenching ?

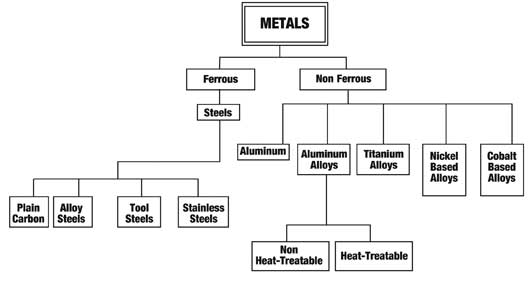

Quenching is a process of cooling a metal very quickly. This is most often done to produce a martensite transformation. In ferrous alloys, this will often produce a harder metal, while non-ferrous alloys will usually become softer than normal.

To harden by quenching, a metal (usually steel or cast iron) must be heated above the upper critical temperature and then quickly cooled. Liquids may be used, due to their better thermal conductivity, such as water, oil, a polymer dissolved in water, or a brine. Upon being rapidly cooled, a portion of austenite (dependent on alloy composition) will transform to martensite, a hard, brittle crystalline structure. The quenched hardness of a metal depends on its chemical composition and quenching method.

In materials science, quenching is the rapid cooling of a workpiece to obtain certain material properties. It prevents low-temperature processes, such as phase transformations, from occurring by only providing a narrow window of time in which the reaction is both thermodynamically favorable and kinetically accessible. For instance, it can reduce crystallinity and thereby increase toughness of both alloys and plastics (produced through polymerization).

Quenching Process

In metallurgy, it is most commonly used to harden steel by introducing martensite, in which case the steel must be rapidly cooled through its eutectoid point, the temperature at which austenite becomes unstable. In steel alloyed with metals such as nickel and manganese, the eutectoid temperature becomes much lower, but the kinetic barriers to phase transformation remain the same. This allows quenching to start at a lower temperature, making the process much easier. Even cooling such alloys slowly in air has most of the desired effects of quenching.

Quenching is an accelerated method of bringing a metal back to room temperature, preventing the lower temperatures through which the material is cooled from having a chance to cause significant alterations in the microstructure through diffusion. Quenching can be performed with forced air convection, oil, fresh water, salt water and special purpose polymers. When quenching in a liquid medium, it is important to stir the liquid around the piece to clear away steam from the surface; steam pockets locally defeat the quench by air cooling until they are cleared away.

Most commonly performed to harden steels, water quenching from a temperature above the austenitic temperature will cause carbon to be trapped inside the austenitic lath, resulting in the hard and brittle martensitic phase. Quench hardening is a mechanical process in which steel and cast iron alloys are strengthened and hardened. These metals consist of ferrous metals and alloys. This is done by heating the material to a certain temperature, dependent upon material, and then rapidly cooling the material. This produces a harder material by either surface hardening or through-hardening varying on the rate at which the material is cooled. The material is then often tempered to reduce the brittleness that may increase from the quench hardening process. Items that may be quenched include gears, shafts, and wear blocks.

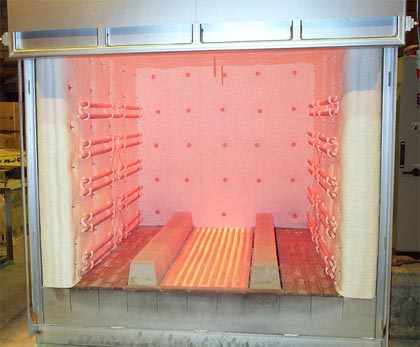

Quenching metals is a progression; the first step is soaking the metal, i.e. heating it to the required temperature. Soaking can be done by air (air furnace), or a bath. The soaking time in air furnaces should be 1 to 2 minutes for each millimeter of cross-section. For a bath the time can range a little higher. Water is one of the most efficient quenching media where maximum hardness is acquired, but there is a small chance that it may cause distortion and tiny cracking. When hardness can be sacrificed, whale, cottonseed and mineral oils are used. The quenching velocity (cooling rate) of oil is much less than water. Intermediate rates between water and oil can be obtained with water.

Before the material is hardened, the microstructure of the material is a pearlite grain structure that is uniform and laminar. Pearlite is a mixture of ferrite and cementite formed when steel or cast iron are manufactured and cooled at a slow rate. After quench hardening, the microstructure of the material form into martensite as a fine, needle-like grain structure.

You might also like

| Heat Treatment Furnaces Heat Treatment Furnaces of Steel Heat treating... | Martensitic Transformation : Mysterious Properties Explained Do you know Martensite Transformation ? Martensite... | Heat Treatment of Tool Steels Heat Treatment of Tool Steels Tool steel... | Aluminum “Hardening” - How it works? Heat Treatment of Aluminum The term “heat... |

Alloy Suppliers

Alloy Suppliers

Aluminum

Aluminum

Aluminum Extrusions

Aluminum Extrusions

Copper-Brass-Bronze

Copper-Brass-Bronze

Nickel

Nickel

Magnets

Magnets

Stainless Steel

Stainless Steel

Stainless Steel Tubing

Stainless Steel Tubing

Steel Service Centers

Steel Service Centers

Titanium

Titanium

Tungsten

Tungsten

Wire Rope

Wire Rope